Exploited Expertise: Enslaved People and Their Equine Skills

Enslaved Horsemen

Before 1865, the horse industry relied on the mental acuity and physical labor of enslaved African Americans. They were valuable assets to their enslavers; so too were their racehorses. In the South, success on the track brought prestige. Often, the hard work and expertise of African American horsemen enabled that success.

Enslaved boys and young men assigned to the horse barn would begin as stable hands and general laborers. They then worked as exercisers, hot walkers, or jockeys. With yet more experience, these enslaved horsemen might become grooms, trainers, or stable managers.

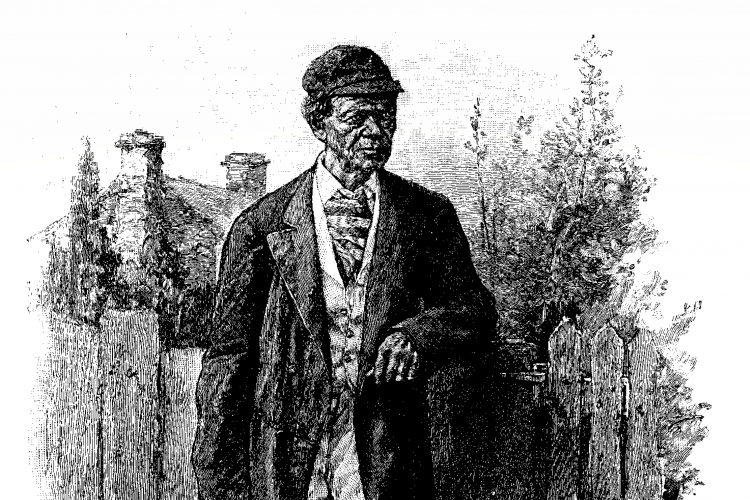

Harry Lewis in Art

The story of Harry Lewis shows how trusted and valuable these men were to their owners. Painter Edward Troye included Harry Lewis in a commissioned painting of his owner’s prize winning horse, Richard Singleton. This cemented Lewis’s prominence in the horse industry. Troye portrayed an impeccably dressed Lewis standing at the horse’s head, wearing a fine tailored suit and top hat.

A Semblance of Freedom

Experienced African American horsemen would often run the stable or train their enslaver's horses. These tasks extended their work beyond the boundaries of their owner’s farms. If it was to the owners advantage, they were sometimes tasked with transporting horses across state lines for sale or stud. Under unique circumstances, owners allowed enslaved horsemen to represent them in decisions about racing, trading, and breeding.

Charles Stewart and Family Ties

The story of enslaved horsemen like Charles Stewart illuminates the psychological complexities of slavery. His owner sent Stewart on a venture to the free state of Pennsylvania and Stewart returned with business successfully concluded. Why didn't he stay there, or try to escape?

Horsemen were far from the only type of enslaved person who had such seeming freedom of movement. Indeed, sending enslaved people on errands was common practice because owners knew that most would return.

The pull of family was enough to ensure the compliance of many enslaved people. When an enslaved man (horseman or otherwise) was bought with his wife, child, or parent, the reason was not altruistic. Moreover, life as a runaway slave was very difficult, even in free states. Faced with no good way out, most enslaved people stayed within the system they knew.

Ownership and Honor

Regardless of their skills, African American horsemen remained enslaved human beings. There was no benevolence in slavery.

Virginia horse owner John Minor Botts thought nothing of burying his jockey Ben in horse manure in the sun to sweat off a few extra pounds before a race. Abuse like this was common practice throughout the South. Yet, Black horsemen were also able to become accomplished and revered members of an unequal society.

Some celebrated the hard work and honor of horsemen, claiming that they were more honest and faithful than white jockeys. In fact, Ansel Williamson (trainer) and Abe Hawkins (jockey) both stayed on to continue in their work at Woodburn Farm even after Emancipation. Williamson’s 1998 selection to the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame is a testament to his professional skill.

Source

International Museum of the Horse. Black Horsemen of the Kentucky Turf: Companion Book to the Exhibit at the International Museum of the Horse. First. Kentucky Horse Park, 2018.

Citation

When citing this article as a source in Chicago Manual of Style use this format: Last name, first name of Author. Chronicle of African Americans in the Horse Industry. n.d. “Title of Profile or Story.” International Museum of the Horse. Accessed date. URL of page cited.